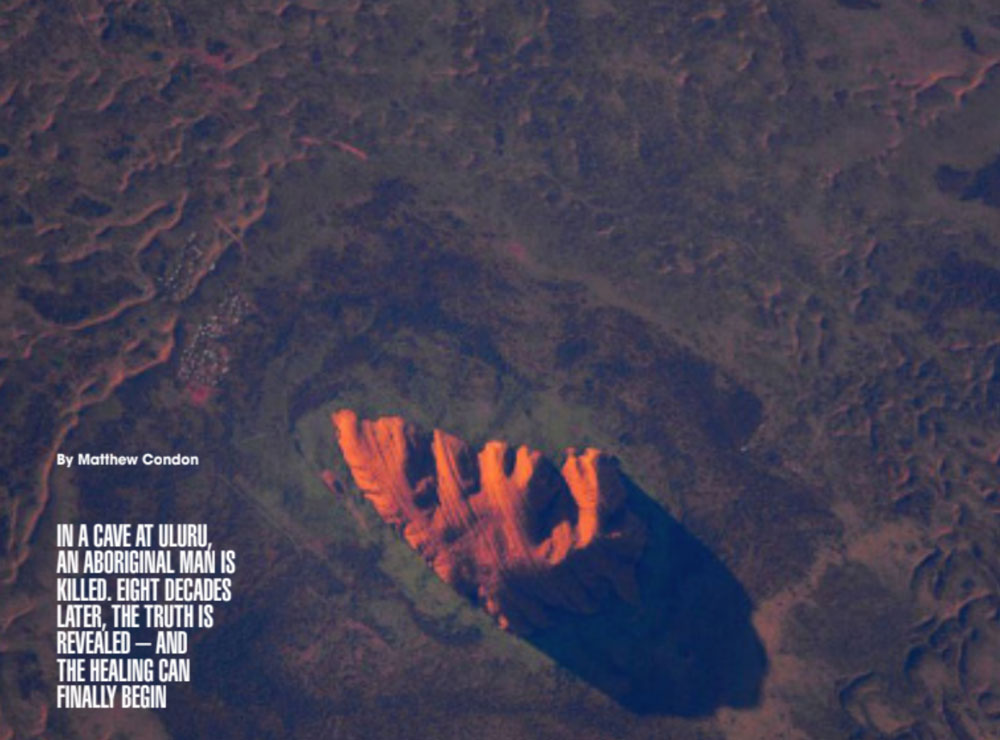

From space, Uluru appears as a rust-coloured shard of rock resting on a piece of deep green velvet cloth, the fabric smooth around the fragment’s immediate perime- ter, then fanning out in gentle rills and folds. And if you study that fragment long enough, in a now famous image taken from 400km above Earth by astronaut Thomas Pesquet aboard the Interna- tional Space Station, your imagination can see things in it. Perhaps a clenched fist. Possibly a distorted face, tilted back and moaning in grief.

Back on terra firma, this sacred sandstone monolith sits 468km by road south-west of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory. Its “gravity of the archaic” has an almost magnetic pull, writes poet and author Barry Hill, and represents an “undeniable statement of the continent’s antiq- uity.” Tighten the focus to Uluru’s southern end and you’ll find the Mutitjulu Waterhole. Here, in the Dreaming, the Kuniya (python) woman avenged her nephew who had been killed by a group of Liru, or brown snakes. She confronted one of the Liru, and in a rage bludgeoned him to death. He dropped his shield near the waterhole during the attack. A boulder remains where it fell.

In 2013, historian Mark McKenna stepped into these ancient stories, the dizzying sacredness and myth and physical awe that for millennia has spun around this geological wonder of the world. Visit- ing the rock for the first time, he thought he might write about “the Centre”, totally unaware he was about to be hijacked by an old murder.